I wrote the "Secure Systems" column in the September/October 2009

IEEE Security and Privacy, which is hitting the streets just about

now. You can read the full column, "Taking Surveillance

out of the Shadows", at

www.mattblaze.org/papers/mab-sec-200909.pdf [pdf]. The subject, familiar to readers here, is

wiretapping gone wrong.

I wrote the "Secure Systems" column in the September/October 2009

IEEE Security and Privacy, which is hitting the streets just about

now. You can read the full column, "Taking Surveillance

out of the Shadows", at

www.mattblaze.org/papers/mab-sec-200909.pdf [pdf]. The subject, familiar to readers here, is

wiretapping gone wrong.

Wiretapping has been controversial lately, often framed, rightly or wrongly, as a zero-sum battle between our right to privacy on the one hand and the needs of law enforcement and intelligence agencies on the other. But in practice, surveillance is about more than policy and civil liberties -- it's also about technology. Reliably intercepting traffic in modern networks can be harder than it sounds. And, time and again, the secret systems relied upon by governments to collect wiretap intelligence and evidence have turned out to have serious problems. Whatever our policy might be, interception systems can -- and do -- fail, even if we don't always hear about it in the public debate.

Indeed, the recent history of electronic surveillance is a veritable catalog of cautionary tales of technological errors, risks and unintended consequences. Sometime mishaps lead to well-publicized violations of the privacy of innocent people. There was, for example, the NSA's disclosure earlier this year that it had been accidently "over-collecting" the communications of innocent Americans. And there was the discovery, in 2005, that the standard interfaces intended to let law enforcement tap cellular telephone traffic had been hijacked by criminals who were using them to tap the mobile phones of hundreds of people in Athens, Greece.

Bugs in tapping technology don't always let in the bad guys; sometimes they keep out the good guys instead. Cryptographers may recall the protocol failures in the NSA's "Clipper" key escrow system [pdf], in which wiretaps could be defeated easily by exploiting a weak authentication scheme during the key setup. More recently, there was the discovery in 2004, by Micah Sherr, Sandy Clark, Eric Cronin and me, that law enforcement intercepts of analog phones can be disabled just by sending a tone down the tapped line [pdf].

What's going on here? It's hard to think of another law enforcement technology beset by as many, or as frequent, flaws as are modern wiretapping systems. No one would tolerate a police force regularly hobbled by exploding guns, self-opening handcuffs, stalled radio cars, or contaminated evidence bags. Yet many of the systems we depend on to track suspected criminals and spies have failed just as spectacularly, if more quietly.

A common factor in these failed systems is that they were designed and deployed largely in secret, away from the kind of engineering scrutiny that, as security engineers know well, is essential for making systems robust. It's a natural enough reflex for law enforcement and intelligence agencies to want to keep their surveillance technology under wraps. But while it may make sense to keep secret who is under surveillance, there's no need to keep secret how. And the track record of current systems suggests a process that is seriously, even dangerously, broken.

Fortunately, unlike some aspects of the debate about wiretapping,

reliability isn't a political issue. The flaws in these systems

cut across ideology. No one is served by defective technology

that spies on the wrong people or that lets criminals, spies, or

terrorists evade legal wiretaps. If surveillance is to

protect us, it has to come out of the shadows.

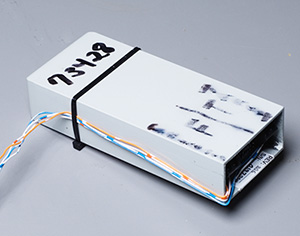

Photo: Law enforcement "loop extender" tap for analog phone lines.