Warrantless wiretapping is back in the news, thanks largely to

Michael Isikoff's cover piece in the December 22 issue of Newsweek. We now know that the principal source for James Risen and Eric Lichtblau's Pulitzer Prize winning

article that broke the story three years ago in the New York Times was a Justice department official named Thomas M. Tamm.

Most of the current attention, naturally,

has focused on Tamm and on whether, as Newsweek's tagline put it, he's

"a hero or a criminal". Having never in my life faced an ethical dilemma on the magnitude of

Tamm's -- weighing betrayal of one trust against the service of another -- I can't

help but wonder what I'd have done in his shoes.

Whistleblowing is inherently difficult, morally ambiguous territory. At best there are

murky shades of gray, inevitably viewed through the myopic lenses

of individual loyalties, fears, and ambitions, to say nothing of the prospect of

life-altering consequences that might accompany exposure.

Coupled with the high

stakes of national security and civil liberties, it's hard not to think about

Tamm in the context of another famously anonymous source, the late

Mark Felt (known to a generation only as Watergate's "Deep Throat").

Warrantless wiretapping is back in the news, thanks largely to

Michael Isikoff's cover piece in the December 22 issue of Newsweek. We now know that the principal source for James Risen and Eric Lichtblau's Pulitzer Prize winning

article that broke the story three years ago in the New York Times was a Justice department official named Thomas M. Tamm.

Most of the current attention, naturally,

has focused on Tamm and on whether, as Newsweek's tagline put it, he's

"a hero or a criminal". Having never in my life faced an ethical dilemma on the magnitude of

Tamm's -- weighing betrayal of one trust against the service of another -- I can't

help but wonder what I'd have done in his shoes.

Whistleblowing is inherently difficult, morally ambiguous territory. At best there are

murky shades of gray, inevitably viewed through the myopic lenses

of individual loyalties, fears, and ambitions, to say nothing of the prospect of

life-altering consequences that might accompany exposure.

Coupled with the high

stakes of national security and civil liberties, it's hard not to think about

Tamm in the context of another famously anonymous source, the late

Mark Felt (known to a generation only as Watergate's "Deep Throat").

But an even more interesting revelation -- one ultimately far more troubling -- can be found in a regrettably less prominent sidebar to the main Newsweek story, entitled "Now we know what the battle was about", by Daniel Klaidman. Put together with other reports about the program, it lends considerable credence to claims that telephone companies (including my alma matter AT&T) provided the NSA with wholesale access to purely domestic calling records, on a scale beyond what has been previously acknowledged.

The sidebar casts new light on one of the more dramatic episodes to leak out of Washington in recent memory; quoting Newsweek:

It is one of the darkly iconic scenes of the Bush Administration. In March 2004, two of the president's most senior advisers rushed to a Washington hospital room where they confronted a bedridden John Ashcroft. White House chief of staff Andy Card and counsel Alberto Gonzales pressured the attorney general to renew a massive domestic-spying program that would lapse in a matter of days. But others hurried to the hospital room, too. Ashcroft's deputy, James Comey, later joined by FBI Director Robert Mueller, stood over Ashcroft's bed to make sure the White House aides didn't coax their drugged and bleary colleague into signing something unwittingly. The attorney general, sick and pain-racked from a rare pancreatic disease, rose up from his bed, gathering what little strength he had, and firmly told the president's emissaries that he would not sign their papers.Like most people, I had assumed that the incident concerned the NSA's interception (without the benefit of court warrants) of the contents of telephone and Internet traffic between the US and foreign targets. That program is at best a legal gray area, the subject of several lawsuits, and the impetus behind Congress' recent (and I think quite ill-advised) retroactive grant of immunity to telephone companies that provided the government with access without proper legal authority.White House hard-liners would make one more effort -- getting the president to recertify the program on his own, relying on his powers as commander in chief. But in the end, with an election looming and the entire political leadership of the Justice Department poised to resign rather than carry out orders they thought to be illegal, Bush backed down. The rebels prevailed.

But that, apparently, wasn't was this was about at all. Instead, again quoting Newsweek:

Two knowledgeable sources tell NEWSWEEK that the clash erupted over a part of Bush's espionage program that had nothing to do with the wiretapping of individual suspects. Rather, Comey and others threatened to resign because of the vast and indiscriminate collection of communications data. These sources, who asked not to be named discussing intelligence matters, describe a system in which the National Security Agency, with cooperation from some of the country's largest telecommunications companies, was able to vacuum up the records of calls and e-mails of tens of millions of average Americans between September 2001 and March 2004. The program's classified code name was "Stellar Wind," though when officials needed to refer to it on the phone, they called it "SW." (The NSA says it has "no information or comment"; a Justice Department spokesman also declined to comment.)While it may seem on the surface to involve little more than arcane and legalistic hairsplitting, that the battle was about records rather than content is actually quite surprising. And it raises new -- and rather disturbing -- questions about the nature of the wiretapping program, and especially about the extent of its reach into the domestic communications of innocent Americans.

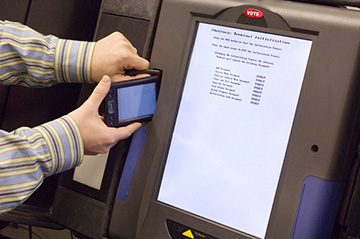

There have been a number of recent reports of touchscreen

voting machines "flipping" voters' choices in early voting in the

US Presidential election. If true, that's a very

serious problem, apparently confirming everyone's worst fears about

the reliability and security of the technology. So what

should we make of these reports, and what should we do?

There have been a number of recent reports of touchscreen

voting machines "flipping" voters' choices in early voting in the

US Presidential election. If true, that's a very

serious problem, apparently confirming everyone's worst fears about

the reliability and security of the technology. So what

should we make of these reports, and what should we do?

In technical terms, many of the problems being reported may be related to mis-calibrated touch input sensors. Touchscreen voting machines have to be adjusted from time to time so that the input sensors on the screen correspond accurately to the places where the candidate choices are displayed. Over time and in different environments, these analog sensors can drift away from their proper settings, and so touchscreen devices generally have a corrective "calibration" maintenance procedure that can be performed as needed. If a touchscreen is not properly accepting votes for a particular candidate, there's a good chance that it needs to be re-calibrated. In most cases, this can be done right at the precinct by the poll workers, and takes only a few minutes. Dan Wallach has an excellent summary (written in 2006) of calibration issues on the ACCURATE web site. The bottom line is that voters should not hesitate to report to poll workers any problems they have with a touchscreen machine -- there's a good chance it can be fixed right then and there.

Unfortunately, the ability to re-calibrate these machines in the field is a double edged sword from a security point of view. The calibration procedure, if misused, can be manipulated to create exactly the same problems that it is intended to solve. It's therefore extremely important that access to the calibration function be carefully controlled, and that screen calibration be verified as accurate. Otherwise, a machine could be deliberately (and surreptitiously) mis-calibrated to make it difficult or impossible to vote for particular candidates.

Is this actually happening? There's no way to know for sure at this point, and it's likely that most of the problems that have been reported in the current election have innocent explanations. But at least one widely used touchscreen voting machine, the ES&S iVotronic, has security problems that make partisan re-calibration attacks a plausible potential scenario.

A group of MIT students made news last week with their discovery of insecurities in Boston's "Charlie" transit fare payment system [pdf]. The three students, Zack Anderson, R.J. Ryan and Alessandro Chiesa, were working on an undergraduate research project for Ron Rivest. They had planned to present their findings at the DEFCON conference last weekend, but were prevented from doing so after the transit authority obtained a restraining order against them in federal court.

The court sets a dangerous standard here, with implications well beyond MIT and Boston. It suggests that advances in security research can be suppressed for the convenience of vendors and users of flawed systems. It will, of course, backfire, with the details of the weaknesses (and their exploitation) inevitably leaking into the underground. Worse, the incident sends an insidious message to the research community: warning vendors or users before publishing a security problem is risky and invites a gag order from a court. The ironic -- and terribly unfortunate -- effect will be to discourage precisely the responsible behavior that the court and the MBTA seek to promote. The lesson seems to be that the students would have been better off had they simply gone ahaed without warning, effectively blindsiding the very people they were trying to help.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation is representing the students, and as part of their case I (along with a number of other academic researchers) signed a letter [pdf] urging the judge to reverse his order.

Update 8/13/08: Steve Bellovin blogs about the case here.

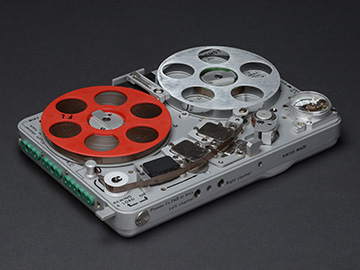

Over-engineered surveillance gadgetry has always held a special (if somewhat perverse, given my professional interests) fascination for me. As a child, I understood that the best job in the world belonged to Harry Caul (and as an adult, it was a thrill to finally meet his real-life counterpart, countermeasures expert Marty Kaiser, last week).

Over-engineered surveillance gadgetry has always held a special (if somewhat perverse, given my professional interests) fascination for me. As a child, I understood that the best job in the world belonged to Harry Caul (and as an adult, it was a thrill to finally meet his real-life counterpart, countermeasures expert Marty Kaiser, last week).

So perhaps it was inevitable when recently, facing a low-grade but severely geeky midlife crisis, I recaptured my youth with the Maserati of 70's spy gear: the Nagra SNST (see photo at right). For decades, this miniature reel-to-reel audio recorder, specially optimized for eavesdropping, was the standard surveillance device, used by just about every law enforcement and intelligence agency that could afford the money-is-no-object price tag. Slightly larger than two iPods, the SNST runs virtually silently for over six hours on two AA batteries, and can record about two hours of voice-grade stereo audio on a 2.75 inch reel of 1/8 inch wide tape. Now largely made obsolete by soulless digital models, the Nagras are built more like Swiss watches than tape recorders. And trust me, now that I own one, I feel twenty years younger.

I bought mine on the surplus market and ended up with a unit from the Missouri State Highway Patrol, where it had been used in drug and other investigations until at least 1996. Why do I know so much about its history?

Because my new surveillance recorder came with a tape.

I had assumed the tape would be blank or erased, but before recording over it a few days ago, I decided to give it a listen just to be sure. Much to my surprise, it wasn't blank at all, but contained a message from the past: "February 8, 1996, I'm Trooper Blunt, Missouri State Highway Patrol..."

The tape, it turns out, was an old evidence recording of a confidential informant being sent out to try to purchase some methamphetamine. But the informant's identity isn't so "confidential" after all: his name, and the name of the guy he was to buy the drugs from, was given right there at the beginning of the tape. The tape they'd eventually sell me a dozen years later.

I made an MP3 of the recording; it's about 42 minutes long and, I must admit, as crime drama goes it's a letdown. It consists almost entirely of the sound of the informant driving to and from the buy location, with no actual transaction captured on tape. No intricate criminal negotiations or high-speed car chases here, I'm afraid. So, although the recording is fairly long, all the actual talking is in the first few minutes, where the officer gives last-minute instructions to the informant. But just in case someone involved still harbors a grudge after 12 years, I've muted out the names of the informant and the suspect from the audio stream. You can listen to the audio here [.mp3 format].

Unfortunately, this isn't the first time that confidential police data has leaked out in this and other ways, and it no doubt won't be the last. Law enforcement agencies routinely do a bad job redacting names and other sensitive information from electronic documents; in May, I discovered deleted figures hidden in the PDF of a Justice Department report on wiretapping. And a few years ago, when my lab was acquiring surplus telephone interception devices for our work on wiretapping countermeasures, some of the equipment we purchased (on eBay) contained old intercept recordings and logs or was configured with suspects' telephone numbers.

None of this should be terribly surprising. It's becoming harder and harder to destroy data, even when it's as carefully controlled as confidential legal evidence. Aside from copies and backups made in the normal course of business, there's the problem of obsolete media in obsolete equipment; there may be no telling what information is on that old PC being sent to the dump, where it might end up, or who might eventually read it. More secure storage practices -- particularly transparent encryption -- can help here, but they won't make the problem go away entirely.

Once sensitive or personal data is captured, it stays around forever, and the longer it does, the more likely it is that it will end up somewhere unexpected. This is one reason why everyone should be concerned about large-scale surveillance by law enforcement and other government agencies; it's simply unrealistic to expect that the personal information collected can remain confidential for very long.

And whatever you do, should you find yourself becoming an informant for the Missouri Highway Patrol, you might want to consider using an alias.

MP3 audio here.

Photo: My new Nagra SNST; hi-res version available on Flickr.

I had a great time yesterday at David Byrne's Playing the Building auditory installation (running through August in the Battery Maritime Building in lower Manhattan). It involves an old organ console placed in the

middle of a semi-abandoned ferry terminal with various actuators hooked up throughout the building. The structure itself -- its pipes, columns, and so on -- makes the actual sound, under the control of whoever is

at the console. You can read more about the project at davidbyrne.com.

I had a great time yesterday at David Byrne's Playing the Building auditory installation (running through August in the Battery Maritime Building in lower Manhattan). It involves an old organ console placed in the

middle of a semi-abandoned ferry terminal with various actuators hooked up throughout the building. The structure itself -- its pipes, columns, and so on -- makes the actual sound, under the control of whoever is

at the console. You can read more about the project at davidbyrne.com.

Anyone can just go in and spend a few minutes playing the building. There's no real way to prepare ahead of time or directly apply expertise with another instrument; to make sound you have to experiment. So every performance by a visitor is by necessity an at least somewhat playful exploration. (There are apparently also occasional scheduled performances by musicians who've actually rehearsed with the contraption, but there wasn't one while I was there yesterday).

The result is surprisingly successful at blurring the distinctions between performer and audience, professional and amateur, work and play, signal and noise. An almost incidental side effect is some interesting, and occasionally hauntingly beautiful, ambient music. It reminded me of some of the early field recordings of Tony Schwartz (a terrific body of work I discovered, sadly, through his recent obituary on WNYC's "On the Media").

Given the nature of the piece, it was a bit incongruous to see almost everyone taking pictures of the console and the space, but hardly anyone recording the sound itself, at least while I was there. Presumably this has something to do with the relative ubiquity of small cameras versus small audio recorders, but I suspect there's more to it than that. The commercial and artistic establishment routinely prohibits "amateur" recording in "professional" performance spaces, and we've become conditioned to assume that that's just the natural order of things. (We're also expected to automatically consent to being recorded ourselves while in those same spaces, but maybe that's another story.) Amateur documentary field recording seems in danger of withering away even as the technology to do it becomes cheaper, better, and more available. In fifty years will we be able to find out what daily life in the early part of this century really sounded like?

Anyway, bucking this trend I happened to have a little pocket digital recorder with me and so I made a couple of brief recordings. (Here, I was cheerfully told, recording is perfectly fine.) Every minute or two a different (anonymous) visitor is at the console (there was a steady line). Most people played with a partner; a few soloed.

Each 256Kbps stereo .mp3 file is about 12 minutes long and about 21MB. I'll post the (huge) uncompressed PCM .wav files to freesound.org shortly.

- Track 1: Left-Right, 3:15pm [.mp3 audio]

Recorded at the center of the main room, facing toward the organ console. There are occasional footsteps, people talking, children running and laughing, etc. (which, I think, are best understood as being part of the "performance"), but the dominant sound here is the building itself being played. This perspective approximates being in the "audience".

.

.

- Track 2: Rear-Front, 3:30pm [.mp3 audio]

Recorded near the console, oriented left channel toward the rear of the room and right toward the front. That is, the stereo image is rotated 90 degrees from the above and the mic position is much closer to the person playing. It includes more (and louder) talking and other sound from audience members, and because of the position some of the building sounds that would be quite loud in the center of the room are barely audible here. This perspective approximates what one hears while actually playing the building from the organ console.

(Note that these were not recorded at the same time; I only had the one recorder with me).

Technical note: All sound was recorded on July 5, 2008 with a handheld Nagra ARES-M miniature digital recorder via the "green band" clip-on XY microphone, in 16bit/48KHz/1536Kbps stereo PCM mode (converted to MP3 with Logic Pro 8).

I was lucky enough to be invited to the first Interdisciplinary Workshop on Security and Human Behavior at MIT this week. Organized by Alessandro Acquisti, Ross Anderson, George Lowenstein, and Bruce Schneier, the workshop brought together an aggressively diverse group of 42 researchers from perspectives across computing, psychology, economics, sociology, philosophy and even photography and skepticism. As someone long interested in security on the human scale [pdf], it was exciting to meet so many like minded people from outside my own field. And judging from the comments on Ross' and Bruce's blogs, there's a lot more interest in this subject than from just the attendees.

There wasn't a single climactic insight or big result from the workshop; the participants mainly gave overviews of their fields or talked about their previously published work. The point was to get people with similar interests but widely different backgrounds talking (and hopefully collaborating) with one another, and it succeeded amazingly well at that. I overheard someone (accurately) comment that many of the kinds of conversations that usually take place in the hallway or the bar at most conferences were taking place in the sessions here.

This was a small and informal event, with no published proceedings or other tangible record, but I made quick-and-dirty sound recordings of most of the sessions, which I'll put up here as I process them.

I apologize for the uneven sound quality (the Frank Gehry sculpture in which the workshop was held was clearly not designed with acoustics in mind, and the speakers weren't always standing near my recorder's microphone on the podium). Audience comments in particular may be inaudible. Keep in mind that these are all big 90 minute MP3 files, about 40MB each, so they are definitely not for the bandwidth-deprived. For concise summaries of the sessions, see Ross Anderson's excellent live-blogged notes here.

Update 7/1/08 8pm: I'm heading back home from the conference now, with all the sound from yesterday already online below. I should have today's files (except the last session) up by late tonight or early tomorrow.

Update 7/1/08 11pm: I've uploaded the rest of the conference audio (except for the final session), all of which is linked from the agenda below. Unfortunately, I had to leave just before the last session (Session 8), so there's no audio for that one; sorry.