Stewart Baker, former director of policy at the Department of Homeland Security, the parent agency of the TSA, took me to task for my recent posting about the new TSA boarding pass scanners being installed at airport security checkpoints.

My observation was that the ID checkpoint is insufficient and in the wrong place; fixing the Schneier/Soghoian attack requires that a strong ID check be performed at the boarding gate, which the new system still doesn't do. Stewart says that the TSA security process doesn't care what flight someone is on as long as they are screened properly and compared against the "no fly" list.

Maybe it doesn't; the precise security goals to be achieved by identifying travelers have never been clearly articulated, which is an underlying cause of this and other problems with our aviation security system. But the TSA has repeatedly asserted that passenger flight routing is very much a component of their name screening process. For example, the regulations governing the Secure Flight program published last October in the Federal Register [pdf] say that "... TSA may learn that flights on a particular route may be subject to increased security risk" and so might do different screening for passengers on those routes. I don't know whether that's true or not, but those are the TSA's words, not mine.

Anyway, Stewart's confusion about the security properties of the protocol, and about my reasons for discussing them notwithstanding, the larger point is that aviation security is a complex (and interesting) problem in the discipline that I've come to understand as "human-scale security protocols".

I first wrote about human scale security as a computer science problem back in 2004 in my paper Toward a broder view of security protocols [pdf]. Such protocols share much in common with the cryptographic authentication and identification schemes used in computing: they're hard to design well and they can fail in subtle and surprising ways. Perhaps cryptographers and security protocol designers have something to contribute toward analyzing and designing better systems here. We can certainly learn something from studying them.

In 2003, Bruce Schneier published a simple and effective attack against the TSA's protocol for verifying a flyer's identity on domestic flights in the US. Nothing was done until 2006, when Chris Soghoian, then a grad student at Indiana University, created an online fake boarding pass generator that made it a bit easier to carry out the attack. That got the TSA's attention: Soghoian's home was raided by the FBI and he was ordered to shut down or face the music. But the TSA still didn't change its flawed protocol, and so for more than five years, despite the inconvenience of long security lines and rigorous checks of our government-issue photo IDs at the airport, it has remained possible for bad guys to exploit the loophole and fly under a fake name. I blogged about the protocol failure, and the TSA's predictably defensive, shoot-the-messenger reaction to it, in this space a couple of years ago.

Well, imagine my surprise yesterday when I noticed something new at Philadelphia International Airport: the TSA ID checker was equipped not just with the usual magnifying glass and UV light, but with a brand new boarding pass reader. The device, which did not yet seem to be in use, apparently reads and validates the information encoded on a boarding pass and displays the passenger name as recorded in the airline's reservation record. According to the TSA blog, boarding pass readers are being rolled out at selected security checkpoints, partly to to enable "paperless" boarding passes on mobile phones, but also to close the fake boarding pass loophole.

Unfortunately, the new system doesn't actually fix the problem. The new protocol is still broken. Even when the security checkpoint boarding pass readers are fully operational, it will still be straightforward to get on a flight under a false name.

I'm not sure how often I'll actually update it, but I've got a Twitter feed now: twitter.com/mattblaze

Even if you can't say it in an SMS message, it still might be worth saying. I suspect I'll still mainly be using this blog.

It's the holiday weekend, so today's (overdue) entry has perhaps

less to do with computer security and crypto than usual.

It's the holiday weekend, so today's (overdue) entry has perhaps

less to do with computer security and crypto than usual.

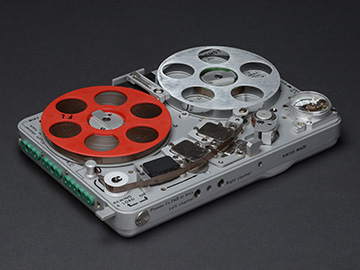

I'm interested in techniques for capturing the ambient sounds of places and environments. This kind of recording is something of a neglected stepchild in the commercial audio world, which is overwhelmingly focused on music, film soundtracks, and similarly "professional" applications. But field recording -- documenting the sounds of the world around us -- has a long and interesting history of its own, from the late Tony Schwartz's magnetic wire recordings of New York city street life in the the 40's and 50's to the stunning natural biophonies hunted down across the world by Bernie Krause. And the Internet has brought together small but often quite vibrant communities of wonderfully fanatic nature recordists and sound hunters. But we're definitely on the margins of the audio world here, specialized nerds even by the already very geeky standards of the AV club.

We tend to take the unique sounds of places for granted, and we may not even notice when familiar soundscapes radically change or disappear out from under (or around) us. And in spite of the fact that high quality digital audio equipment is cheaper and more versatile than ever, hardly anyone thinks to use a recorder the way they might a digital camera. Ambient sound is, for most purposes, as ephemeral as it ever was. I commented last year in this space on the strange dearth of available recordings of David Byrne's Playing the Building audio installation; Flickr is loaded with photos of the space, but hardly any visitors thought to capture what it actually sounded like. And now, like so many other sounds, it's gone.

Anyway, I've found that making good quality stereo field recordings carries its own challenges besides the obvious ones of finding interesting sounds and getting the right equipment to where they are. In particular, most research on, and commercial equipment for, stereo recording is focused (naturally enough) on serving the needs of the music industry. There the aim is to get a pleasing reproduction of a particular subject -- a musician, an orchestra, whatever -- that's located in a relatively small or at least identifiable space, usually indoors. "Ambience" in music recording has to do mainly with capturing the effect of the subject against the space. Any sounds originating from the local environment are usually considered nothing more than unwelcome noise, blemishes to be eliminated or masked from the finished product.

But the kind of field recording I'm interested in takes the opposite approach -- the environment is the subject. Most of the standard, well-studied stereo microphone configurations aren't optimized for capturing this. Instead, they're usually aiming to limit the "recording angle" to the slice where the music is coming from and to reduce the effects of everything else. There are some standard microphone arrangements that can work well for widely dispersed subjects, but most of the literature discusses them in the context of indoor music recording. It's hard to predict, without actually trying it, how a given technique can be expected to perform in a particular outdoor environment. If experience is the best teacher, it's pretty much the only one available here.

Compounding the difficulty of learning how different microphone configurations perform outdoors is the surprising paucity of controlled examples of different techniques. There are plenty of terrific nature recordings available online, but people tend to distribute only their best results, and keep to themselves the duds recorded along the way. For the listener, that's surely for the best, of course, but it means that there are lamentably few examples of the same sources recorded simultaneously with different (and documented) techniques from which to learn and compare.

And so I've slowly been experimenting with different stereo techniques and making my own simultaneous recordings in different outdoor environments. In doing this, I can see why similar examples aren't more common; making them involves hauling around more equipment, taking more notes, and spending more time in post-production than if the goal were simply to get a single best final cut. But the effort is paying off well for me, and perhaps others can benefit from my failures (and occasional successes). So I'm collecting and posting a few examples on this web page [link], which I will try to update with new recordings from time to time. But mostly, I'd like to encourage others to do the same; my individual effort is really quite pale in the grand scheme of things, limited as it is by my talent, equipment, and carrying capacity.

My sample clips, for what they're worth, can be found at www.mattblaze.org/audio/soundscapes/.

Once again I was lucky enough to be invited to this year's Interdisciplinary Workshop on Security and Human Behavior at MIT this week. Organized by Alessandro Acquisti, Ross Anderson, and Bruce Schneier, the workshop aims to bring together an aggressively diverse group of researchers from perspectives in computing, psychology, economics, sociology, and philosophy. (I blogged about last year's workshop here.)

This is a small and informal event, with no published proceedings or other tangible record. But Bruce Schneier, Adam Shostack and Ross Anderson are liveblogging the sessions.

As with last year, I ended up making quick-and-dirty sound recordings of the sessions, which I'll put up here as I process them. (I apologize for the uneven audio quality; the recording conditions were hugely suboptimal. And I didn't know I'd was supposed to be doing this until five minutes before the first session, using a recorder and microphone I luckily happened to have in my backpack.)

Update 6/12/09 1745: All session audio is now online after the fold below.

Today's

New York Times is reporting that the NSA has been "over-collecting" purely domestic telephone and e-mail traffic as part of its warrentless wiretap program. According to Eric Lichtblau and James Risen's

article, part of the reason for the unauthorized

domestic surveillance was technological:

Today's

New York Times is reporting that the NSA has been "over-collecting" purely domestic telephone and e-mail traffic as part of its warrentless wiretap program. According to Eric Lichtblau and James Risen's

article, part of the reason for the unauthorized

domestic surveillance was technological:

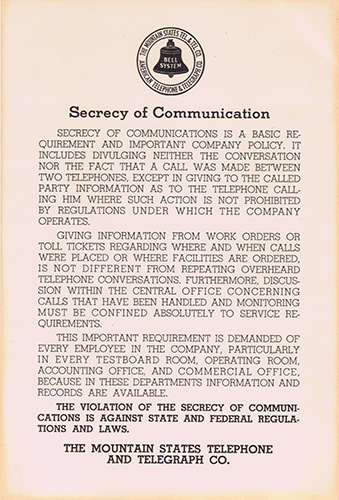

Officials would not discuss details of the overcollection problem because it involves classified intelligence-gathering techniques. But the issue appears focused in part on technical problems in the N.S.A.'s ability at times to distinguish between communications inside the United States and those overseas as it uses its access to American telecommunications companies' fiber-optic lines and its own spy satellites to intercept millions of calls and e-mail messages.As disturbing as this report is, the sad fact is that domestic over-collection was a readily predictable consequence of the way the NSA apparently has been conducting some of its intercepts. According to court filings in the EFF's lawsuit against AT&T, the taps for international traffic are placed not, as we might expect, at the trans-oceanic cable landings that connect to the US, but rather inside switching centers that also handle a great deal of purely domestic traffic. Domestic calls are supposed to be excluded from the data stream sent to the government by specially configured network filtering devices supplied by the NSA.One official said that led the agency to inadvertently "target" groups of Americans and collect their domestic communications without proper court authority. Officials are still trying to determine how many violations may have occurred.

This is, to say the least, a precarious way to ensure that only international traffic would be collected, and an especially curious design choice given the NSA's exclusively international mandate. My colleagues and I have been warning of the risks of this strange architecture for several years now, perhaps most prominently in this IEEE Security and Privacy article [pdf]. And I raised the point on a panel with former NSA official Bill Crowell at last year's RSA conference; as I wrote in this space then:

There's a tendency to view warrantless wiretaps in strictly legal or political terms and to assume that the interception technology will correctly implement whatever the policy is supposed to be. But the reality isn't so simple. I found myself the sole techie on the RSA panel, so my role was largely to to point out that this is as much an issue of engineering as it is legal oversight. And while we don't know all the details about how NSA's wiretaps are being carried out in the US, what we do know suggests some disturbing architectural choices that make the program especially vulnerable to over-collection and abuse. In particular, assuming Mark Klein's AT&T documents are accurate, the NSA infrastructure seems much farther inside the US telecom infrastructure than would be appropriate for intercepting the exclusively international traffic that the government says it wants. The taps are apparently in domestic backbone switches rather than, say, in cable heads that leave the country, where international traffic is most concentrated (and segregated). Compounding the inherent risks of this odd design is the fact that the equipment that pans for nuggets of international communication in the stream of (off-limits) domestic traffic is apparently made up entirely of hardware provided and configured by the government, rather than the carriers. It's essentially equivalent to giving the NSA the keys to the phone company central office and hoping that they figure out which wires are the right ones to tap.Architecture matters. As Stanford Law professor Larry Lessig famously points out, in the electronic world "code is law". Arcane choices in how technologies are implemented can have at least as much influence as do congress and the courts. As this episode demonstrates, any meaningful public debate over surveillance policy must include a careful and critical examination of how, exactly, it's done.

Eight Clay County, Kentucky election officials were charged last week with conspiring to alter ballots cast on electronic voting machines in several recent elections. The story was first reported on a

local

TV station and was featured on the

election integrity site BradBlog.

According to the indictment [pdf],

the conspiracy

allegedly included, among other things, altering ballots cast

on the county's ES&S iVotronic touchscreen voting machines.

Eight Clay County, Kentucky election officials were charged last week with conspiring to alter ballots cast on electronic voting machines in several recent elections. The story was first reported on a

local

TV station and was featured on the

election integrity site BradBlog.

According to the indictment [pdf],

the conspiracy

allegedly included, among other things, altering ballots cast

on the county's ES&S iVotronic touchscreen voting machines.

So how could this have happened?

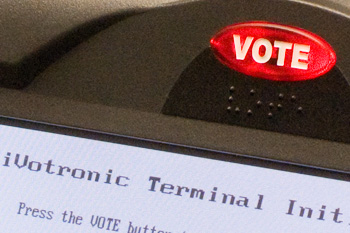

The iVotronic is a popular Direct Recording Electronic (DRE) voting machine. It displays the ballot on a computer screen and records voters' choices in internal memory. Voting officials and machine manufacturers cite the user interface as a major selling point for DRE machines -- it's already familiar to voters used to navigating touchscreen ATMs, computerized gas pumps, and so on, and thus should avoid problems like the infamous "butterfly ballot". Voters interact with the iVotronic primarily by touching the display screen itself. But there's an important exception: above the display is an illuminated red button labeled "VOTE" (see photo at right). Pressing the VOTE button is supposed to be the final step of a voter's session; it adds their selections to their candidates' totals and resets the machine for the next voter.

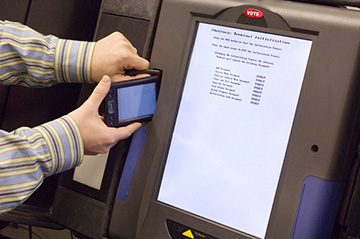

The Kentucky officials are accused of taking advantage of a somewhat confusing aspect of the way the iVotronic interface was implemented. In particular, the behavior (as described in the indictment) of the version of the iVotronic used in Clay County apparently differs a bit from the behavior described in ES&S's standard instruction sheet for voters [pdf - see page 2]. A flash-based iVotronic demo available from ES&S here shows the same procedure, with the VOTE button as the last step. But evidently there's another version of the iVotronic interface in which pressing the VOTE button is only the second to last step. In those machines, pressing VOTE invokes an extra "confirmation" screen. The vote is only actually finalized after a "confirm vote" box is touched on that screen. (A different flash demo that shows this behavior with the version of the iVotronic equipped with a printer is available from ES&S here). So the iVotronic VOTE button doesn't necessarily work the way a voter who read the standard instructions might expect it to.

The indictment describes a conspiracy to exploit this ambiguity in the iVotronic user interface by having pollworkers systematically (and incorrectly) tell voters that pressing the VOTE button is the last step. When a misled voter would leave the machine with the extra "confirm vote" screen still displayed, a pollworker would quietly "correct" the not-yet-finalized ballot before casting it. It's a pretty elegant attack, exploiting little more than a poorly designed, ambiguous user interface, printed instructions that conflict with actual machine behavior, and public unfamiliarity with equipment that most citizens use at most once or twice each year. And once done, it leaves behind little forensic evidence to expose the deed.

Warrantless wiretapping is back in the news, thanks largely to

Michael Isikoff's cover piece in the December 22 issue of Newsweek. We now know that the principal source for James Risen and Eric Lichtblau's Pulitzer Prize winning

article that broke the story three years ago in the New York Times was a Justice department official named Thomas M. Tamm.

Most of the current attention, naturally,

has focused on Tamm and on whether, as Newsweek's tagline put it, he's

"a hero or a criminal". Having never in my life faced an ethical dilemma on the magnitude of

Tamm's -- weighing betrayal of one trust against the service of another -- I can't

help but wonder what I'd have done in his shoes.

Whistleblowing is inherently difficult, morally ambiguous territory. At best there are

murky shades of gray, inevitably viewed through the myopic lenses

of individual loyalties, fears, and ambitions, to say nothing of the prospect of

life-altering consequences that might accompany exposure.

Coupled with the high

stakes of national security and civil liberties, it's hard not to think about

Tamm in the context of another famously anonymous source, the late

Mark Felt (known to a generation only as Watergate's "Deep Throat").

Warrantless wiretapping is back in the news, thanks largely to

Michael Isikoff's cover piece in the December 22 issue of Newsweek. We now know that the principal source for James Risen and Eric Lichtblau's Pulitzer Prize winning

article that broke the story three years ago in the New York Times was a Justice department official named Thomas M. Tamm.

Most of the current attention, naturally,

has focused on Tamm and on whether, as Newsweek's tagline put it, he's

"a hero or a criminal". Having never in my life faced an ethical dilemma on the magnitude of

Tamm's -- weighing betrayal of one trust against the service of another -- I can't

help but wonder what I'd have done in his shoes.

Whistleblowing is inherently difficult, morally ambiguous territory. At best there are

murky shades of gray, inevitably viewed through the myopic lenses

of individual loyalties, fears, and ambitions, to say nothing of the prospect of

life-altering consequences that might accompany exposure.

Coupled with the high

stakes of national security and civil liberties, it's hard not to think about

Tamm in the context of another famously anonymous source, the late

Mark Felt (known to a generation only as Watergate's "Deep Throat").

But an even more interesting revelation -- one ultimately far more troubling -- can be found in a regrettably less prominent sidebar to the main Newsweek story, entitled "Now we know what the battle was about", by Daniel Klaidman. Put together with other reports about the program, it lends considerable credence to claims that telephone companies (including my alma matter AT&T) provided the NSA with wholesale access to purely domestic calling records, on a scale beyond what has been previously acknowledged.

The sidebar casts new light on one of the more dramatic episodes to leak out of Washington in recent memory; quoting Newsweek:

It is one of the darkly iconic scenes of the Bush Administration. In March 2004, two of the president's most senior advisers rushed to a Washington hospital room where they confronted a bedridden John Ashcroft. White House chief of staff Andy Card and counsel Alberto Gonzales pressured the attorney general to renew a massive domestic-spying program that would lapse in a matter of days. But others hurried to the hospital room, too. Ashcroft's deputy, James Comey, later joined by FBI Director Robert Mueller, stood over Ashcroft's bed to make sure the White House aides didn't coax their drugged and bleary colleague into signing something unwittingly. The attorney general, sick and pain-racked from a rare pancreatic disease, rose up from his bed, gathering what little strength he had, and firmly told the president's emissaries that he would not sign their papers.Like most people, I had assumed that the incident concerned the NSA's interception (without the benefit of court warrants) of the contents of telephone and Internet traffic between the US and foreign targets. That program is at best a legal gray area, the subject of several lawsuits, and the impetus behind Congress' recent (and I think quite ill-advised) retroactive grant of immunity to telephone companies that provided the government with access without proper legal authority.White House hard-liners would make one more effort -- getting the president to recertify the program on his own, relying on his powers as commander in chief. But in the end, with an election looming and the entire political leadership of the Justice Department poised to resign rather than carry out orders they thought to be illegal, Bush backed down. The rebels prevailed.

But that, apparently, wasn't was this was about at all. Instead, again quoting Newsweek:

Two knowledgeable sources tell NEWSWEEK that the clash erupted over a part of Bush's espionage program that had nothing to do with the wiretapping of individual suspects. Rather, Comey and others threatened to resign because of the vast and indiscriminate collection of communications data. These sources, who asked not to be named discussing intelligence matters, describe a system in which the National Security Agency, with cooperation from some of the country's largest telecommunications companies, was able to vacuum up the records of calls and e-mails of tens of millions of average Americans between September 2001 and March 2004. The program's classified code name was "Stellar Wind," though when officials needed to refer to it on the phone, they called it "SW." (The NSA says it has "no information or comment"; a Justice Department spokesman also declined to comment.)While it may seem on the surface to involve little more than arcane and legalistic hairsplitting, that the battle was about records rather than content is actually quite surprising. And it raises new -- and rather disturbing -- questions about the nature of the wiretapping program, and especially about the extent of its reach into the domestic communications of innocent Americans.

There have been a number of recent reports of touchscreen

voting machines "flipping" voters' choices in early voting in the

US Presidential election. If true, that's a very

serious problem, apparently confirming everyone's worst fears about

the reliability and security of the technology. So what

should we make of these reports, and what should we do?

There have been a number of recent reports of touchscreen

voting machines "flipping" voters' choices in early voting in the

US Presidential election. If true, that's a very

serious problem, apparently confirming everyone's worst fears about

the reliability and security of the technology. So what

should we make of these reports, and what should we do?

In technical terms, many of the problems being reported may be related to mis-calibrated touch input sensors. Touchscreen voting machines have to be adjusted from time to time so that the input sensors on the screen correspond accurately to the places where the candidate choices are displayed. Over time and in different environments, these analog sensors can drift away from their proper settings, and so touchscreen devices generally have a corrective "calibration" maintenance procedure that can be performed as needed. If a touchscreen is not properly accepting votes for a particular candidate, there's a good chance that it needs to be re-calibrated. In most cases, this can be done right at the precinct by the poll workers, and takes only a few minutes. Dan Wallach has an excellent summary (written in 2006) of calibration issues on the ACCURATE web site. The bottom line is that voters should not hesitate to report to poll workers any problems they have with a touchscreen machine -- there's a good chance it can be fixed right then and there.

Unfortunately, the ability to re-calibrate these machines in the field is a double edged sword from a security point of view. The calibration procedure, if misused, can be manipulated to create exactly the same problems that it is intended to solve. It's therefore extremely important that access to the calibration function be carefully controlled, and that screen calibration be verified as accurate. Otherwise, a machine could be deliberately (and surreptitiously) mis-calibrated to make it difficult or impossible to vote for particular candidates.

Is this actually happening? There's no way to know for sure at this point, and it's likely that most of the problems that have been reported in the current election have innocent explanations. But at least one widely used touchscreen voting machine, the ES&S iVotronic, has security problems that make partisan re-calibration attacks a plausible potential scenario.

A group of MIT students made news last week with their discovery of insecurities in Boston's "Charlie" transit fare payment system [pdf]. The three students, Zack Anderson, R.J. Ryan and Alessandro Chiesa, were working on an undergraduate research project for Ron Rivest. They had planned to present their findings at the DEFCON conference last weekend, but were prevented from doing so after the transit authority obtained a restraining order against them in federal court.

The court sets a dangerous standard here, with implications well beyond MIT and Boston. It suggests that advances in security research can be suppressed for the convenience of vendors and users of flawed systems. It will, of course, backfire, with the details of the weaknesses (and their exploitation) inevitably leaking into the underground. Worse, the incident sends an insidious message to the research community: warning vendors or users before publishing a security problem is risky and invites a gag order from a court. The ironic -- and terribly unfortunate -- effect will be to discourage precisely the responsible behavior that the court and the MBTA seek to promote. The lesson seems to be that the students would have been better off had they simply gone ahaed without warning, effectively blindsiding the very people they were trying to help.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation is representing the students, and as part of their case I (along with a number of other academic researchers) signed a letter [pdf] urging the judge to reverse his order.

Update 8/13/08: Steve Bellovin blogs about the case here.