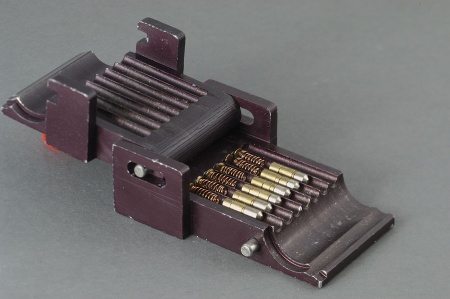

Figure 1. A Best SFIC lock cylinder.

21 April 2003

"Small Format Interchangeable Core (SFIC)" locks, first made by Best Access Systems, are popular with medium- and large- scale institutional lock users in the US. These locks offer moderate resistance against manipulation and forceful attack, support large master key systems, are of good general quality, and are available for a wide range of lock configurations. The most important feature of these cylinders, however, is the ease with which the end-user can manage them. A special control key unlocks and allows removal from the front of the lock of the core, which contains the keyway and pins. New cores can be swapped in and out in a few seconds as required, without the need for tools or special locksmithing skills. Most users keep on hand a supply of extra cores that are rotated through to support routine re-keying.

SFIC locks come in six and seven pin versions and can use the same keys for either (they are "tip stopped," so the keys for six pin locks stick out of the keyway a bit further). About 25 different keyways are commonly used; the lock shown in Figure 1 is for the "L" keyway. Pins for SFIC locks are slightly smaller than those used in conventional cylinders, and tolerances are comparatively tight. A variety of depth systems are used, supporting up to 10 distinct bitting heights per pin position with no MACS restriction. This allows up to 10,000,000 distinct keys per keyway (although there are effectively fewer in practice, due to tolerance errors and phantom keys in master systems).

The control key (cut on the same blank and otherwise indistinguishable from a regular key) turns about 20 degrees clockwise to disengage a retaining tab that locks the core in the housing. The core pulls out while the housing stays in place in the door (the one shown in Figure 2 is a standard-size screw-in mortise cylinder).

Housings for SFIC locks have two fingers (extending about halfway down the length of the cylinder) that engage the core's plug and that are linked with the locking mechanism. In addition to standard mortise cylinders, SFIC housings are also manufactured for rim cylinders, key-in-knob locks, padlocks, cabinet locks, electrical switches, etc.

Operating keys (which can be, and typical are, mastered) rotate the lock plug. Note the two holes at the back of the plug in Figure 4, which mate with the fingers in the housing, and the retaining tab (running halfway along the length of the core), which locks the core into the housing (and which remains in the locked state when an operating key is used).

Control keys (which can also be mastered, but rarely are) can rotate the plug only about 20 degrees but also disengage the retaining tab (shown in Figure 5 in the unlocked state), allowing the core to be pulled out from or installed into a lock housing.

The plug (left in Figure 6) in SFIC locks consists of two parts: an inner plug (which has the two holes in the back that mate with the housing fingers) surrounded by a control sleeve (which has the retaining tab). In this photo, the inner plug has been pulled out (by two pin positions). There are two separate shear lines formed by this arrangement. Operating keys line up pin stack cuts at the inner shear line (which allows 360 degree rotation of the plug), while control keys line up pin stack cuts at the outer shear line (which allows retraction of the retaining tab).

Because the two shear lines are separated by slightly more than the maximum bitting height of a key, any given cut can only reach one of the two shear positions. Each pin stack must therefore have two sets of cuts -- one for each shear line -- stacked one on top of the other. Each shear line is keyed (and can be mastered) separately, and a key that lines up cuts for some pins at the operating shear line and cuts for other pins at the control shear line will not operate the lock at all. (In this respect, SFIC locks are similar to "master ring" cylinder designs). Note that the bitting of a control key at any given position might be higher, lower, or the same as an operating key; the only requirement is that the complete control key bitting cannot also be used as an operating key.

The two shear lines can make SFIC locks difficult to manipulate (pick) with conventional tools, because the attacker will usually set some of the pin stacks at the operating shear line and others at the control shear line (which means that even though all of the pins appear to be set, the lock will not operate). In fact, assuming randomly distributed keys, equal friction on the plug and control sleeve, and no mastering, a six pin core with all pins set will only actually open an average of one out of 64 times, and a seven pin core only one out of 128 times. (In practice, it is a bit easier, because unequal friction between the control sleeve and the plug tends to transfer torque more to one shear line than the other. Also, TPP mastering of the operating keyspace means that a given pin is twice as likely to set at the operating shear line than the control shear line). Compounding the difficulty are the small and heavily warded keyways and the tight manufacturing tolerances. Somewhat surprisingly, spool, serrated, and other "security" pin designs are not typically used (though Best now offers them as an option).

The holes in the bottom of the control sleeve are intended to allow insertion of a punch tool that forces the pin stacks out of the top of the core, enabling cores to be emptied and re-pinned without disassembly (there are corresponding holes in the bottom of the core's shell).

These holes also create a manipulation vulnerability, because they allow use of a special tool that puts torque on the control sleeve without also creating a shear force at the operating shear line (as a conventional torque tool or key does). This allows these locks to be picked to the control position (relatively) easily without inadvertently setting some pins to the operating position. Once picked to the control position, the core can be removed (and disassembled and decoded if desired), which exposes the fingers in the lock housing (which can then be rotated with, e.g., a screwdriver).

The torque tool in Figure 8 has three little "fingers" spaced to fit the holes at the bottom of the control sleeve, which effectively puts torque on the control sleeve but no shear force at the (inner) operating shear line. The fingers are long enough to engage the control sleeve but not so long that they protrude into the holes in the shell (which would prevent any rotation).

A conventional torque tool can be modified to produce this tool; commercial products are also available. Note that different thicknesses and widths are required to fit the various SFIC keyways, and shims may be required in the keyway to get the proper fit and good leverage necessary to avoid applying torque to the operating shear line. The only current commercial maker of these tools of which I'm aware is Peterson Manufacturing (shown here is their "thin" SFIC tool). The design was originally due to Gerry Finch.

Unauthorized removal of an SFIC core can represent a more serious potential security threat than conventional lock picking or even the compromise of a master key. In particular, once a core is removed, its pins can be decoded to yield the control key for the system, which is typically equivalent in scope to the top-level master key, and sometimes even spans across multiple master systems.

A special tool ejects the pins through the top of the core (no disassembly with a follower tool is required) and allows decoding. The model in Figure 9 is made by A-1; other vendors produce similar devices.

Once the pin stacks are ejected, they are kept intact in order in slots in the decoder block, and can be measured easily. A control key can then be decoded and cut that can remove other cores in the system. Decoding the control key is especially straightforward; it can be unambiguously determined from a single core simply by measuring the topmost pin of each pin stack. Hence the loss of a single lock in such systems is a very serious threat (padlocks are an especially vulnerable target).

The pins in Figure 10 are for a six pin lock, mastered at the operating shear line with a TPP format and not mastered at the control shear line (this is a typical configuration). Note that each pin stack has four segments (producing two operating cuts and one control cut).

I devised a simple modification to the control sleeve to prevent the use of the Finch-style torque tool. Wider holes in the control sleeve do not give the torque tool's fingers a surface to engage but still allow the insertion of the ejector pin. (The crude prototype in Figures 11 and 12 was done by hand with a Dremel tool, but still works). Obviously, it would be preferable if the manufacturers modified the design of the sleeves in a similar way. (Actually, newer Arrow cores do not suffer from this weakness, as the control sleeve does not go all the way to around the plug.)

Images taken with a Nikon D-100 digital camera with a Nikkor

85mm 1:2.8D tilt/shift macro lens (with Kenko extension tube).

Lit by electronic flash and various reflectors.

All images and text Copyright © 2003 by Matt Blaze. All rights reserved. You may not copy, modify or use these images or text, in whole or in part, for any commercial or non-commercial purpose without permission.

21 April 2003; revised 22 April 2003